A month before William Lyon Mackenzie's Patriot forces began planning, executing, and bungling invasions of Canada, Patriotes in Lower Canada (Quebec) waged battles of their own. One band of rebels even dealt the British a minor defeat.

The factors that created an environment for rebellion in Lower Canada closely resembled those in Upper Canada—a group of English elites kept thwarting the ideals and policies of a reform-oriented elected assembly. Language and cultural differences added to the Lower Canada troubles.

Among the principal Lower Canada reform leaders were Louis-Joseph Papineau (October 7, 1786-September 23, 1871), Dr. Wolfred Nelson (July 10, 1791-June 17, 1863), and Dr. Robert Nelson (August 8, 1794-March 1, 1873). As Anglophones advocating for the rights of the Francophone majority, the Nelson brothers stood out from the majority of French-Canadian Patriotes.

On November 30, 1837, Colonel Gore returned to Saint-Denis. The Patriotes had dispersed. The town surrendered without a fight. Out of spite, the British sacked the town and set 50 homes aflame.

Most rebels fled from the invading army, but Chénier and a core of determined fighters barricaded themselves in a convent, church, rectory, and manor in the center of the village.

Colborne, with his vastly superior force and artillery, systematically attacked and overran each building occupied by Chénier's men. The remaining Patriotes held out in the church. The British smashed their way in and set it on fire to drive the Patriotes out. Many fleeing rebels, including Chénier were killed as they jumped from the burning church. The battle left 70 dead Patriotes and three dead British. (Some sources say the British ignored a flag of surrender but that is likely propaganda.)

Aside: The battle destroyed the church, except for its facade. The rebuilt church includes the original facade. It still shows the impact marks of British cannonballs and musket fire.

In the days that followed, British soldiers and English militia terrorized the countryside around Saint-Eustache, burning and looting several villages, and making sure to destroy houses belonging to known and suspected rebel leaders.

The British military sledgehammer put an end to the Lower Canada rebellion in 1837; but, the fight was not over.

The factors that created an environment for rebellion in Lower Canada closely resembled those in Upper Canada—a group of English elites kept thwarting the ideals and policies of a reform-oriented elected assembly. Language and cultural differences added to the Lower Canada troubles.

Among the principal Lower Canada reform leaders were Louis-Joseph Papineau (October 7, 1786-September 23, 1871), Dr. Wolfred Nelson (July 10, 1791-June 17, 1863), and Dr. Robert Nelson (August 8, 1794-March 1, 1873). As Anglophones advocating for the rights of the Francophone majority, the Nelson brothers stood out from the majority of French-Canadian Patriotes.

|  |

Dr. Wolfred Nelson and Louis-Joseph Papineau in their later years

Civil Disobedience Ignites 1837 Rebellion

On October 23, 1837, Dr. Wolfred Nelson led 5,000 Patriotes in a peaceful assembly to protest English political restrictions. He held the event despite a law forbidding such public gatherings. The assembly adopted a set of American-style republican resolutions. In response, the British charged Wolfred and 25 other Patriote leaders with treason on November 16 and began making arrests.Patriotes Win Battle at Saint-Denis

Wolfred, Papineau, and other Patriotes took refuge in the rebel-sympathetic village of Saint-Denis, southeast of Montreal, and prepared for battle. The British obliged by sending Colonel Charles Gore and 300 regulars to subdue them. After marching through mud, cold, and freezing rain, Gore's force confronted 800 dry and determined rebel fighters just after dawn on November 23, 1837. After several hours of fighting, with ammunition running low and his men weather weary, Gore ordered a retreat. The battle caused about one dozen casualties on both sides. |

| Painting of the Battle of Saint-Denis |

Patriotes Massacred at Saint-Charles

Two days later, British Colonel George Wetherall led 420 regulars on an attack of Saint-Charles, a rebel-held town near Saint-Denis. The Patriote defenders consisted of just 60 to 80 armed men and none of the principal Patriote leaders. Wetherall's men charged and quickly overran the rebel defenses. Some rebels retreated, while others raised their hands in surrender. As the British walked toward the surrendering Patriotes, other rebels opened fire, killing three British soldiers. This treachery enraged the British and they slaughtered every Patriote fighter they could find, leaving 56 dead. |

| Painting of the Battle of Saint-Charles |

Patriotes Defeated at Saint-Eustache

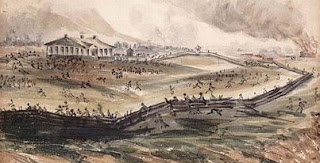

On December 14, 1837, General John Colborne, commander-in-chief of the British armed forces in North America, led an army of 1,500 regulars and militia to the village of Saint-Eustache, west of Montreal. Facing him were 800 Patriotes, of which only about 200 were armed. Leading them was Jean-Olivier Chénier (December 9, 1806 – December 14, 1837), a young reform-minded physician.| Painting of the Battle of Saint-Eustache |

Colborne, with his vastly superior force and artillery, systematically attacked and overran each building occupied by Chénier's men. The remaining Patriotes held out in the church. The British smashed their way in and set it on fire to drive the Patriotes out. Many fleeing rebels, including Chénier were killed as they jumped from the burning church. The battle left 70 dead Patriotes and three dead British. (Some sources say the British ignored a flag of surrender but that is likely propaganda.)

Aside: The battle destroyed the church, except for its facade. The rebuilt church includes the original facade. It still shows the impact marks of British cannonballs and musket fire.

In the days that followed, British soldiers and English militia terrorized the countryside around Saint-Eustache, burning and looting several villages, and making sure to destroy houses belonging to known and suspected rebel leaders.

The British military sledgehammer put an end to the Lower Canada rebellion in 1837; but, the fight was not over.

2 comments:

This was very helpful for my Quebec History class and also alot more insightful and detailed than something found in a textbook. Thank you!

I'm glad this site proved useful. Thanks

Post a Comment